The

Six City-recognized neighborhood associations make up the

[1] From the Data Analysis Sub-zones, Mid Region Council of Governments (MRCOG), U S Census, 2000.

[2] From the City of

In consultation with the planning team, the Coalition committed to carrying out a process based on Philip Herr’s Swamp Yankee methods to develop and implement a community–based vision. Following the Swamp Yankee Planning model, the

Residents and business owners who represented important perspectives and interests in the community were systematically contacted and recruited during the month before the first workshop. The executive committee of the 4th and Montaño Area Improvement Coalition identified an initial list of key community leaders to be recruited to participate. The four facilitation team members contacted these individuals to invite them to participate and ask for referrals to other residents and business owners to contact. The facilitation team kept track of addresses and interests for each person contacted and referred in a matrix that separated the area into five geographic areas (NW, NE, South of Montaño, and Outside the Area) and four interest groups (Seniors, Youth, Renters, and Business) that eventually totaled 145 residents and business owners/managers and developers. The goal was to recruit participation from 7-10 members in each of these affinity groups.

[1] For more detail on the Swamp Yankee model, please see Appendix X, “Negotiating a Vision for the Heart of Albuquerque’s

At some point in the recruitment process, this categorization was further refined to break into geographic areas that almost fit neighborhood association boundaries. Lee Acres and

While business owners and managers and developers showed interest in the workshops and enthusiasm about attending, most likely many could not justify taking the time away from work to attend a process that at best might not benefit them for some time. Some may have questioned the tie between their business and a visioning process, and it is possible that some simply don’t have much interest in area improvements or loyalty to this particular area. Out of 58 business owners/managers or developers, only seven attended the first workshop, with one additional business owner attending the second workshop, primarily because his business supplied lunch for the group.

The pool of renters was considerably smaller than other pools, as the area has few rental units. In addition, the original list of key community members identified by the executive committee only included one renter (of a house in the Los Alamos neighborhood), which indicates that renters were not as well-connected to the social network that extended from the executive committee. This supposition is not too surprising, as renters typically have not been in the area as long as other residents, which contributes to the lack of time to make these social connections, but as a group, renters also tend to be less actively engaged in the community, as many likely do not see their position as long-term. Repeated calls to the apartment complex manager did not lead to any contact names.

As for youth, while fifteen were contacted, many were involved in other activities, and several were unwilling to commit to an all-day workshop on a Saturday during the summer. Several had to go to weekend jobs.

Sixty-five people signed in at the first workshop, including six public officials or city planners. Forty-four signed in at the second workshop, including one public official and three city planners. Based on a cross-check of both lists, 81 people participated in total, so there was an overlap of at least 28 people who came to both workshops, including four public officials and planners.

Group Participation from Sign-in List at Workshop I

| Affinity Groups | Participants |

| 5: “West” (Gavilan/Guadalupe Village) | 4 |

| 6: “West of | 2 |

| 7: Seniors | 6 |

| 8: | 11 |

| 9: South of Montaño | 8 |

| 10: Lee Acres | 7 |

| 11: Business/Developers | 7 |

| 12: Out of Area | 3 |

| * Not from Contact List | 8 |

| **From Contact List but unknown affinity | 2 |

| Total | 58 |

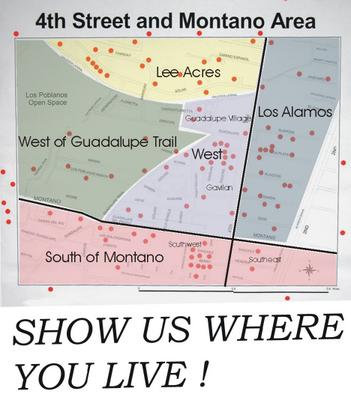

At each workshop, participants were asked to indicate with a red dot where they live or work on the same map of the area. Participants from outside the area were asked to put a dot off the map in the direction of their home. The map of where residents live shows 91 total dots in the area. Compared to the sign-in list, at least 10 people across the two workshops did not sign in but did indicate where they lived on the map.

| Geographic Areas | Dots |

| South of Montano | 21 |

| SW | 19 |

| SE | 2 |

| West | 20 |

| West of | 8 |

| Lee Acres | 19 |

| | 23 |

| Out of Area | 13 |

| N | 4 |

| S | 2 |

| E | 2 |

| W | 5 |

| Total | 104 |

Assessing the representation of the Hispanic community at the workshops is problematic, as demographic data were not collected. A count of Spanish surnames, itself a problematic indicator of ethnicity, shows that while 33 individuals from the contact list (31 families) were contacted and invited to participate, only 15 attended either the first or second workshop. Two of these individuals were not on the original contact list. At best, 50% of those with Spanish surnames contacted actually attended a workshop, which is better than the 39% success rate for the overall contact list (145 contacted, 57 signing in). Of the individuals who signed in at either the first or second workshop, only 20% had Spanish surnames.

Overall, 17 people signed in at one of the workshops who were not on the original contact matrix, which represents 23% of those signing in at the workshops. Information for these participants is limited to their names and the overall number of dots placed on the “Show us where you live” map, which had 91 total dots for both workshops, while only 81 people signed in. Only two of these individuals had Spanish surnames. One was the wife of the business owner delivering lunch. This information calls into question the idea of whether it was only the executive committee who did not have ties to Hispanic residents in the area. Again, firm conclusions cannot be drawn on the basis of Spanish surnames alone. The lack of information for those not on the contact list also complicates counting the numbers of individuals in each affinity group. The counts listed below do NOT include those signing in who were not recruited from the contact list.

It is also important to note that by nature of being from the original contact list, more is known about the participants, so they are counted throughout the course of this analysis. Those not from the contact list, which we can assume also means outside of the immediate social network of the executive committee but perhaps tied to it on a secondary level, do not show up in the subsequent analysis of the groups. It is also possible these residents heard about the workshops through the media or the mass mailing to all households. They represent an important segment of the population – those not immediately connected but active enough to show up to a Saturday workshop once they obtain the information through possibly impersonal media. This population, or perhaps this percentage, could be expected to participate in future planning activities given similar notice. One can assume that personal contact and recruitment would improve the success rate with these individuals.

At the initial community visioning workshop, each geographic area and each interest group were seated at separate tables with the assumption that they would share common concerns and goals. Each of the tables had an assigned facilitator to guide the discussion through a series of four maps of the entire area. The first map asked participants to identify the places special to them. The second map asked for good and bad happenings or trends in the area. The third map focused on a utopian vision. Residents could dream about what their area should be like regardless of political or economic reality. The fourth map asked for priority actions that should be taken in the real world of political and economic restraints to move toward the ideal vision. During the lunch break, maps from each of the tables were displayed in gallery style, and participants were encouraged to tour all of the maps and compare other interests to their own. The afternoon was spent reporting each group’s findings. A facilitator recorded the common items and themes, and an urban designer drew a composite map of the common physical elements and improvement suggestions.

COMING NEXT: Discussion of what the Workshop I maps show.

No comments:

Post a Comment