DISCLAIMER:

This is an initial draft of a masters thesis in Community and Regional Planning.

If you're gonna read it, GIVE ME COMMENTS! Better to get comments now than at my thesis defense.

(Encoruragement/questions also welcomed -- craved -- generally begged for.) Thanks!Over 30 years ago, a Montaño river crossing linking Albuquerque’s east side with the fast-growing residential development on the Rio Grande’s Westside was first proposed and studied. In 1995, after twenty years of opposition, controversy, and protracted legal battles involving all levels of government, the decision to build the bridge was finally made, a deal was cut with neighborhoods to the south for a 2-lane bridge, trees were felled, and construction began. Two years later, the bridge was opened, and the impact on the immediate North Valley residences was dramatic and worsened steadily over time. No one could have known that thirty years after the initial proposal, an unnamed neighborhood would come together in a strategy of community visioning to counter the unintended but all-too-foreseeable effects.

The story of this neighborhood visioning is part of several simultaneous histories. First, it is part of a history of tokenism and citizen participation in a planning process whose logger-head debates and unproductive lawsuits resulted in a group of people who have never known each other, and without much besides traffic fury in common, realizing that they had been collectively duped and deciding to seek a solution that normally arises out of an established community, which because of the divisiveness of the Montaño bridge – separating these residents physically, politically, and culturally from each other and the rest of the Valley – does not apply to them.

Secondly, it is part of a conflict between interests advocating Westside growth and those who favor focusing growth on the eastside to avoid the ecological impact of river crossings. The current Albuquerque mayor, Martin Chavez, is the most recent incarnation of Westside advocates, and not inconsequently, also happened to be serving as Mayor in 1995 when the Montaño Bridge decision was finally made and construction on a 2-lane bridge wide enough for 4 lanes of traffic began. As soon as he took office for the second time in 2001, Mayor Chavez promised/threatened (depending on which side of the river you live) to restripe the bridge to 4 lanes and open it to full traffic capacity. Whether true or not, countervailing perception is that Marty Chavez and his real-estate/development cronies stand with the most to gain from Westside development. It is also no coincidence that Mayor Chavez formerly represented the West Side in his stint as New Mexico State Senator.

Thirdly, it is part of a broader history of Albuquerque’s growth. From its first incarnations, Albuquerque has always been home to a debate about its center and where growth should be in relation. Constantly split between physical and cultural identities, from the first Old Town to the New Town of the Railroad Era in the late 1800s, then the Downtown/Uptown division between east mesa and downtown property owners when the “Big I” was laid out at the intersection of E-W Interstate 40 and N-S Insterstate 25 in the 1960s, Albuquerque seems destined for diametrical debates about growth.

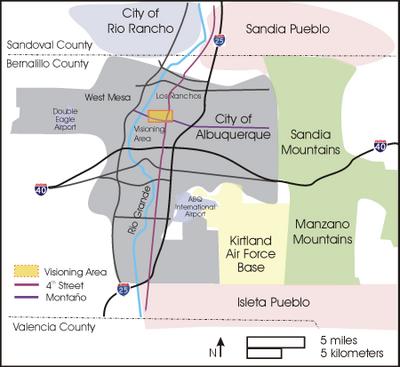

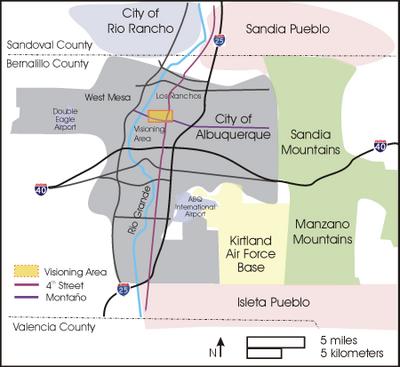

The latest incarnation involves the same issues. Hemmed in by the Sandia and Manzano mountains to the east, Kirtland Airforce Base and Isleta Pueblo to the south, and Sandia and Santa Ana Pueblos to the north, Albuquerque’s growth pressures, having filled in the eastside mesa, now push development onto the mesa west of the Rio Grande. Property owners on the Westside and members of the Chamber of Commerce argue that growth on the west mesa – the only direction Albuquerque can really grow unfettered – demands more bridge access to connect them to economic activity on the eastside. As the debate over restriping the Montaño Bridge to four lanes heats up, it should not be surprising to learn that vacant land at the intersection of Interstate 25 and Montaño is on the verge of development with big-box shopping centers featuring Sam’s Club, Target, and Lowe’s Home Improvement. The debate no longer includes downtown, because it has been rendered economically defunct from losing past debates. Downtown is left with the entertainment and cultural crumbs of economic activity, while real estate speculators and developers rake in profits from vacant lot construction on Albuquerque’s west and north sides.

It is clear to most observers that City coffers, developer profits, and Westside residents stand to gain from this type and shape of growth. What is less clear are the answers to the follow-up questions: What is the cost of this growth, and who pays?

Thirty years ago, when the need for yet another bridge across the river was first debated, city leaders wanted the bridge on Candelaria Road, which at the time was a much busier street and served as one of the main roads in Albuquerque’s North Valley. The City got so far as to take down the cottonwoods lining the street and prepared Rio Grande Boulevard for an at-grade crossing. However, the very fact that Candelaria served strong neighborhoods meant that it had the most vociferous protection from vocal residents with established neighborhood associations and political representation. When it became clear that these neighbors could not be ignored or bought off, city leaders looked farther north for another possible bridge road. Montaño, long a sleepy road serving rural and sparsely-populated areas to the west of 4th Street, looked like a good candidate. While all North Valley residents opposed a river crossing, residents near Montaño were not organized in visible political groups. Montaño is the last major thoroughfare in the City’s North Valley. Past it to the North, the municipality of Los Ranchos de Albuquerque begins. City leaders exploited this chink in jurisdictional armor and shoved the bridge decision through -- after a twenty-year fight.

Neighborhoods near Candelaria were spared the worst of the traffic impacts because they were able to successfully oppose the proposal to put a bridge at the termination of Candelaria, precisely because, to convolute Gertrude Stein’s famous complaint about L.A., there was a there there. Because there was a there there, there was also a neighborhood visible and powerful enough to fight to preserve their there and successfully negotiate with the City. In exchange for their agreement to stop their opposition to

any bridge crossing, these neighborhoods brokered an agreement for the City to begin planning processes for their areas – partly to counter future effects of changes to the Valley they knew would come from an additional river crossing and partly to further strengthen and protect their already strong neighborhoods.

Residents near Montaño were not so lucky. Montaño was chosen for the bridge because there wasn’t a there there, and because the bridge went in, there still isn’t. North Valley neighborhoods near Montaño have been fragmented since they were developed after World War II. Prior to this development, the area was large farms and ranches, protected by their distance from downtown and the limited number of roads connecting them to other places. As the city grew north, large tracts of formerly agricultural lands were converted into subdivisions built at different times, in different styles, layouts, and densities. Many of these neighborhoods were still being built when the Montaño Bridge was first proposed, which is one reason why they were not yet politically established enough to oppose it.

Even as late as 1995, Montaño dead-ended in Simms fields next to the Rio Grande bosque preserve. There was a small church, a small residential neighborhood called Adobe lane, and although there were residents, a sense of history, and a rural sense of place, there was no name for the area, and no established political identity. Even if city leaders had wanted token participation or buy-in from residents in this area, no one knew they were there, or was pressured to care. Had they had a name, or a neighborhood association, someone might have asked them what they thought. The neighbors to the south near Candelaria spoke up. Los Ranchos fought the bridge from the north. This sparsely populated, nebulous area of new subdivisions and still-productive farms near Montaño and 4th Street did not have a political or community voice with which to speak.

In addition to Montaño, the only other major thoroughfare serving these neighborhoods is 4th Street, a centuries old north-south road once part of the Pan American highway, for three centuries part of the El Camino Real, and most recently part of the pre-1937 alignment of Route 66 linking Chicago with Los Angeles. Despite this historic significance, the corridor has been neglected and in decline for decades, taking its first hit when Central took over as Route 66 and again when the Big I shifted the city’s center to Uptown. Since the opening of the Montaño Bridge in 1997, increased traffic resulting from Westside growth and development at the intersection of Montaño and I-25 have decreased safety and a sense of place for residents, pedestrians, and motorists. Local small businesses, traditionally the heart of 4th Street, have gradually closed or moved away, leading to a deterioration of property values and quality of life for surrounding neighborhoods.

The most recent threat from the Mayor to restripe the Montaño Bridge to 4 lanes has served as the impetus motivating a group of residents from neighborhoods surrounding the 4th and Montaño intersection to work toward getting in front of further detrimental effects on their part of the North Valley. Despite their fragmentation, these neighborhoods are united by the fact that they were all left out of the political debate about the Montaño Bridge ten years ago. Unlike their neighbors to the south, they were the only ones not covered by a City plan – then or since. They are united by being orphans, as well as united in being cut off from Montaño Boulevard and sharing the disproportionate traffic impacts on 4th Street, now the only access into and out of their neighborhoods. Not only are they the ones most affected by traffic pains, they are the only ones who have never received the benefits or attention from a City plan.

In 2001, a group of neighbors from the Los Alamos addition, a neighborhood directly north of Montaño and east of 4th Street, first met to strategize about how to counter the effects of the Mayor’s threat to restripe the bridge to 4 lanes. Knowing they did not have the immediate opposition they would need to stop the restriping all together, they decided to buy some time while getting themselves and the larger area organized. Their strategy was simple and brilliant: stall the city by getting it to agree to putting a plan in place – opening an opportunity to organize the neighborhoods with the City footing the bill – before the bridge could be widened. Arguing that their area took the majority of the impact from increased traffic at 4th and Montaño, and that theirs was the only North Valley neighborhood NOT to get a plan out of the original bridge deal, not to mention the fact that the deal itself was made for a 2-lane not a 4 lane bridge, this group, calling itself the 4th and Montaño Area Improvement Coalition, met with the Mayor and garnered an agreement for a three-prong planning process: 1) a series of community visioning workshops, 2) a design charrette based on the vision, and 3) a sector plan that would include zoning and design guidelines.

Not only did they argue on multiple fronts for multiple outcomes, their motives behind this particular strategy were also multifold. Partly, these residents wanted to provide a process that would include all neighborhoods in the area as an organizing strategy. If they could agree on a vision, then they could argue with more clarity for what they want and bargain from a stronger position with one voice (“As a community, we can get this done.” – heard at Executive Committee Meeting). Partly, these residents want to test their own vision for the area against their neighbors’ to see whether they are in alignment and how much opposition to their ideas there might be. Simultaneously, this process is also part of a planning strategy, that the process itself should result in a city plan and implementation steps that will serve efforts to improve the area and move toward revitalization based on the community’s vision.

Above all, this strategy reframed the debate about the Montano Bridge from simply a Westside versus Eastside dispute (in which North Valley residents have been called elitists or NIMBYs) to a comprehensive conversation about what's good for the entire area, shifting the emphasis from Montano as a bridge road to include 4th Street, adding the entire north-south corridor, as well as its historical importance over time.

In the summer of 2004, two community workshops were held, led from the side by a team of private facilitators. The first workshop, held July 31 from 9 am – 3 pm, was focused on surfacing ideas for a community vision. Small groups were separated according to geographic area, with one additional group for elderly residents, one for youth (in theory, at least – in practice, not enough youth showed up for an entire group, so they joined the group for their neighborhood areas), and one for businesses. A facilitator in each group led a conversation to produce a series of maps for the entire area with these four foci, one per map: 1) special places, 2) good and bad happenings, 3) utopian visions, and 4) priority actions. During the report back for each of the groups, the community vision began to take shape in four categories: 1) identity, 2) trails, 3) economic revitalization, and 4) traffic.

The follow-up workshop on August 21 from 9 am – 3 pm separated into small groups based on these categories in order to develop more detailed vision, identify action plans, and begin to organize sub-committees to take the necessary next steps.

Stay tuned for the discussion of IDENTITY. To be written tonight...